Perfume by Patrick Süskind

The only podcast I listen to with eager dedication is Writing Excuses. Hosted by a merry band of mostly science fiction and fantasy authors with frequent guest authors, their craftsmanship and tutelage also includes book-of-the-week reading recommendations. Author Mary Robinette-Kowal challenged herself for a year to only read non-American authors. Her co-host, author Dan Wells recommended Perfume by Patrick Süskind, with a most straightforward subtitle – The Story of a Murderer.

Wells’ lavish description of Süskind’s lavish writing sold me in an instant. And translator John E. Woods does not get nearly enough credit for this many-splendored endeavor.

While much will inevitably be lost in translation people from different cultures still experience structure and story differently regardless of the language in which they read. A commitment to global citizenship is a compassionate necessity in a shrinking world. But it can also make you a better writer. While most Burners coming back from Black Rock City will proselytize hallucinogens to open your mind, I prefer Robinette Kowal’s suggestion of reading authors from cultures and nations besides your own if you’re looking to grow as a writer and as a human.

Enter the weird and pseudo-scientific tale of Enlightenment-era Paris where our protagonist is born in a fetid open-air market, the fifth child to be unceremoniously discarded by his syphilitic mother into the rubbish with fish heads and entrails. If you are reading this book from anywhere with indoor plumbing and penicillin it is easy to forget how wretchedly foul daily life was not so very long ago. It is an unexpected and putrid assault on the senses and the sensibilities of any sentient book-lover who romanticizes Paris as the locus of all worldly sophistication. Human history always has an underbelly. And it reeked in 18th-century Paris. This is not Chanel No 5 and the black-and-white 1950s Paris of Doisneau. This Paris is all wet hay and chamber pots and sulphur chimneys and manure, mutton fat and congealed blood from slaughterhouses, spoiled cabbage and moldy wood, sour milk and tumorous disease – to list but some of the repulsiveness Süskind says, ” … there reigned in the cities a stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women.”

Our hero’s quest is a strange journey from his scentless infancy in an orphanage through his indentured servitude in hide-tanning into his perfuming apprenticeship.

Spoiler(ish) alert: in order to craft the world’s most perfect scent, the apprentice perfumer believes it can only be extracted from young dead girls, who, presumably, naturally emit the loveliest scent found anywhere in nature. I took the required year of introductory biology and one online astronomy course in college. So my science background obviously falls shy of being able to speak about the plausibility of the overarching premise of oil absorbing odors to then be distilled and bottled.

This is not an uplifting read. Our main character is not so much the next person you meet in Heaven as he is Raskolnikov with a purpose and an olfactory gift that defies science. It is equal parts classism, nihilism and misanthropy. Our protagonist suffers from a form of philosophy I’d never heard of: Absurdism, in which mere mortals struggle to find meaning in life. Camus and Kierkegaard apparently offer only three options: suicide, a spiritual belief in the hereafter or acceptance of the absurd.

Grenouille, our most peculiar protagonist unequivocally rejects the spiritual: “There was not the least notion of God in his head. He was not doing penance nor waiting for some supernatural inspiration. He had withdrawn solely for his own personal pleasure, only to be near himself. No longer distracted by anything external, he basked in his own existence and found it splendid. He lay in his stony crypt like his own corpse, hardly breathing, his heart hardly beating – and yet lived as intensively and dissolutely as ever a rake had lived in the wide world outside.”

This is his simultaneous sojourn into a figurative suicide, in which he literally just hibernates in a cave for years, subsisting by eating the occasional lizard or snake.

But ultimately, his purpose becomes clear to him, as though dating back to his birth.

“The cry that followed his birth, the cry with which he had brought himself to people’s attention and his mother to the gallows, was not an instinctive cry for sympathy and love. That cry … was the newborn’s decision against love and nevertheless for life.”

Despite the functional caste system of the time, he is undeterred from his call.

“The idea was, of course, one of perfectly grotesque immodesty. There was nothing, absolutely nothing, that could justify a stray tanner’s helper of dubious origin, without connections or protection, without the least social standing, to hope that he would get so much as a toehold in the most renowned perfume shop in Paris …”

More than just accepting the absurdity of life, and his life specifically, he is resolute in his singular purpose.

“He was enchanted by their meaningless perfection; and at no time in his life, either before or after, were there moments of such truly innocent happiness as in those days when he playfully and eagerly set about creating fragrant landscapes, still lifes, and studies of individual objects. For he soon moved on to living subjects.”

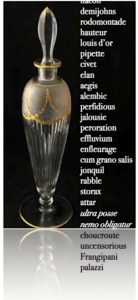

Society seems to equate magical realism with Marquez, and we associate it with Kahlo and Rousseau, even Lewis Carroll sometimes. We tend to think of it is as beautifully colorful rather than colorfully macabre. But if you would like to wade through the misadventures of an 18th century murderer, I’ve prepared a vocab list to help you prep ahead for your journey, honored here with one of the first words I learned from this book was ‘flacon’ – an old-timey perfume bottles that I grew up covetting as the epitome of glamorous women getting ready for glamorous nights out. Women who had lighted vanities in bedrooms that could only be called boudoirs. (It is apparently any glass bottle with a stopper for a top.)

Society seems to equate magical realism with Marquez, and we associate it with Kahlo and Rousseau, even Lewis Carroll sometimes. We tend to think of it is as beautifully colorful rather than colorfully macabre. But if you would like to wade through the misadventures of an 18th century murderer, I’ve prepared a vocab list to help you prep ahead for your journey, honored here with one of the first words I learned from this book was ‘flacon’ – an old-timey perfume bottles that I grew up covetting as the epitome of glamorous women getting ready for glamorous nights out. Women who had lighted vanities in bedrooms that could only be called boudoirs. (It is apparently any glass bottle with a stopper for a top.)

Süskind’s vocabulary and story-telling are equally pungent. Unlike some American public figures this German author really is highly educated. He really does have the best words. This book is in fact the reason I started using blank paper as bookmarks so I could jot down all the words I don’t know and need to look up later. The list is at least twice as long as I’ve included here. I recommend the practice and the book.